Recently, The Globe and Mail published an article about “Fast Furniture” – a perhaps more innocuous cousin of fast fashion, but one that is still resulting in hundreds of thousands of tonnes of old furniture ending up Canadian landfills each and every year.

While the article discussed many novel strategies to help minimize furniture waste, such as investing in more durable vintage furniture, or identifying retailers that offer more sustainable furniture options, what was conspicuously absent from the article is what can be done with fast furniture at its end of life.

Who is Furniture Bank?

Contrary to the views expressed by the article, “fast furniture” is not inevitably destined for the landfill – in fact, it may have a critical role to play in helping and empowering Canada’s most vulnerable people. Enter Furniture Bank, a Greater Toronto Area based charity and social enterprise that helps marginalized and at risk families furnish their homes. Furniture bank accepts gently used furniture and other household items, distributing them to families in need. This includes both commercial and residential mattress returns (a notoriously difficult to manage material at end of life), as well as tracking and monitoring all goods and their ultimate disposition. Unlike many other waste collectors, Furniture Bank conducts a full mass balance of all materials being managed by their program, allowing them the means to quantify both diversion totals and social return on investments. The impact of Furniture Bank, particularly with respect to supporting the province’s long term circular economy goals, was highlighted by the city of Toronto in their long term waste management strategy ( https://www.toronto.ca/long-term-waste-strategy//supporting-torontos-circular-economy/)

While the Furniture Bank program has been immensely successful, helping divert more than 1500 tonnes of material from Toronto landfills annually (and 10,000 tonnes to date), there is still a significant opportunity for growth and improvement moving forward. This is a national opportunity. Furniture Bank works with Furniture Link who specializes in brokering reuse projects between retailers and manufacturers and furniture banks across Canada to ensure fast furniture overstock and returns is prioritized through organizations like Furniture Bank. It has recently brought Furniture Bank and IKEA together to support reuse projects as part of IKEAs People + Planet 2030 strategy.

At present, there is no prescriptive legislation for how furniture waste should be managed in the province. In most instances, households carry the physical and financial responsibility for transporting furniture waste to landfills, and will often rely on “junk” collectors to provide this service. While furniture waste generation is highly variable (depending on locality, season etc.), a review of Ontario waste audits suggests that furniture and white good waste makes up approximately 5% of the overall waste stream, representing approximately 125,000 tonnes of material annually.

Opportunities for collaboration with external stakeholders

Municipalities have traditionally played a limited role in managing these items, but what role can a municipality play in not only supporting keeping these items out of landfills, but maximizing social and environmental outcomes as well?

Often times, when we think about waste management issues, it tends to be through the fairly myopic lens of diversion. While keeping furniture out of landfills poses significant environmental and economic benefits, a truly sustainable solution *must* consider a social dimension as well. The three tenants of sustainability (environment, economy and community (social)) dictate that all dimensions of sustainability are of equal importance, but that is rarely the case in issues surrounding waste. In fact, in the City of Toronto’s own long term waste management plan, there is no consideration for how diversion can be used to promote socially beneficial outcomes for Torontonians.

While it may not be readily apparent as to the connection between social sustainability and waste, it is impossible to isolate the two from one another. In fact, socio-economic inequity often first manifests itself in issues related to waste. Lower income communities have fewer opportunities to participate in waste management programs (i.e. lack of organics program in apartment buildings), face higher rates of illegal dumping, and reduced levels of service relative to more affluent communities. Perhaps most egregious, is that these communities are often situated in closer proximity to waste related hazards such as landfills and transfer stations. In many ways, our waste management decisions have adversely affected vulnerable communities, creating a two tiered system of “haves and have nots” with respect to service delivery.

Diversion with a purpose

Why organizations such as Furniture Bank are so critical, is that they provide a unique opportunity to “Divert with a purpose”, not only keeping thousands of tonnes of furniture out of landfills, but providing our most vulnerable groups with furniture and other households items that turn a “house into a home”.

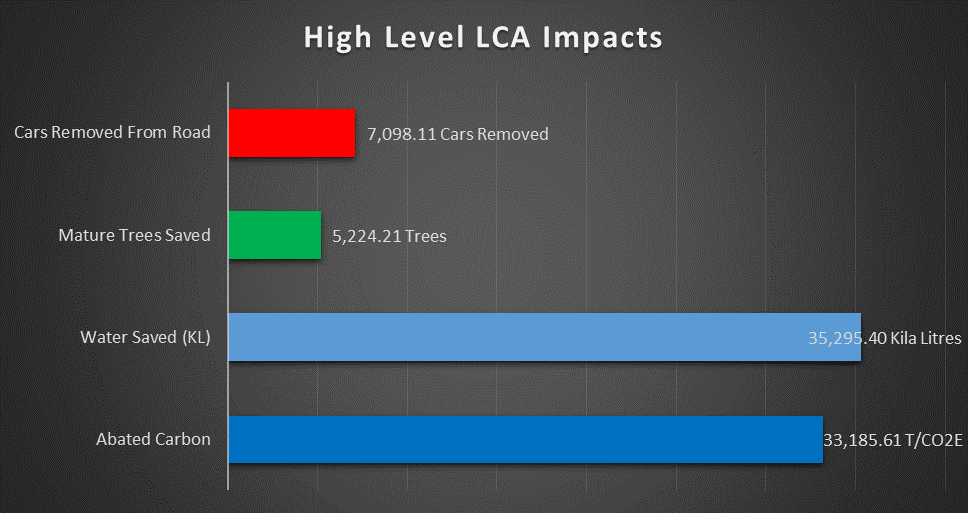

Figure 1 below summarizes the high level life cycle analysis impacts attributable to environmental impact of Furniture Bank in Toronto.

Fig 1: LCA Impacts

The environmental benefits attributable to textile diversion are immediately apparent, with Furniture Bank abating in excess of 33 thousand tonnes of carbon from our environment. Major retailers such as IKEA have also recognized this opportunity for improvement, entering into a pilot program with Furniture Bank and Furniture Link to find ways to financially support the organization and its mandate. The current arrangement ensures that Furniture Bank is paid for the transportation of returned and reused furniture, which are then provided to families in need. In return, Furniture Bank supports IKEA in monitoring and measuring the impacts of their program, and helping the retailer in meeting its ambitious People Planet 2030 zero waste goals.

However, the impacts of Furniture Bank and what it does cannot be truly appreciated until you see first hand what impact it has on vulnerable groups – in short, the story isn’t just about diversion, but transforming lives. I had the pleasure of visiting Furniture Bank at their offices last year. Despite my many years working in the waste sector, my attention did not immediately go to the hundreds of household items that were being repaired, repurposed and restored. Instead, I was drawn to the families that were visiting the facility that day, picking out items that they would eventually use to furnish their new homes. It was a tremendously humbling experience to see the role that unwanted home furnishings can play in giving confidence and hope to families who are often going through very uncertain and unpredictable times.

Achieving the improbable: win/win solutions in the world of waste

Promoting and supporting organizations such as Furniture Bank is a rare win/win in the world of waste. As noted prior, Furniture Bank has diverted thousands of tonnes of furniture and other household items from landfills, which results in a direct savings to municipalities who are grappling with burgeoning waste generation and limited available landfill capacity.

Many companies would prefer to landfill home furnishings and avoid creating grey markets, but companies like Furniture Link are have demonstrated that shifting the costs and unwanted goods into a network of furniture banks across Canada can create a compelling win/win solution for a companies bottomline and the community.

As we look to increase diversion rates, we have to ask ourselves two questions: 1) Where will the next diverted tonne come from? And 2) What do I want achieve by diverting more material?

Conventional means and mediums of diversion (i.e. Blue Box) have been exhausted – the next diverted tonne is not likely to come from newsprint or cardboard, but from organics, textiles and furniture. In addition to finding new opportunities to divert material, what are we trying to achieve by doing so? Is it good enough just to keep material out of landfills, or should we seek to identify ways to maximize economic and social outcomes as well?

“Diverting with a purpose” – municipalities (and the province) can play a critical role in supporting waste collectors such as Furniture Bank that have a mission beyond “managing waste”, and look to improve the lives and well-being of Ontarians. The opportunity isn’t just about the hundreds of thousands of tonnes of material not currently being diverted, but the tens of thousands people that benefit through strategic prioritization of material streams and waste collectors.

The task at hand is enormous – but so is the opportunity. Furniture Bank continues to play a critical role in diverting furniture waste from landfills, but will play an even bigger role in findings ways to support and build more resilient communities. They are the living embodiment of the phrase “One man’s trash is another’s treasure”.

The Globe & Mail article suggest fast furniture should have the same bad reputation as fast fashion. When furniture banks are engaged in prioritizing reuse, repair, and repurposing of unwanted furniture they can significantly reduce the negative aspects of fast furniture.